The protectionism of Luis Arce's government prevents greater investment from the private sector beyond Chinese and Russian capital that promotes the direct extraction of lithium (EDL), an innovative production method, although without scientific support.

It is not news that lithium is the mineral of the future for several industries. Its usefulness in the manufacture of energy reactors and batteries for electric vehicles makes it the so-called “white gold”. For this reason, producing countries and world powers are in constant negotiation to ensure the greatest benefits from the new industry.

Bolivia is a clear example: the highland country has abundant reserves of lithium and even has the largest deposit in the world, located in the Uyuni salt flat. By July 2023, its reserves were estimated at 23 million tons of lithium. It is in this scenario where the government of Luis Arce, with a socialist tendency, is inclined to agree on investments with rival countries of the United States such as China and Russia. Many of these operations involve novel methods that promise to increase production levels and, therefore, profits.

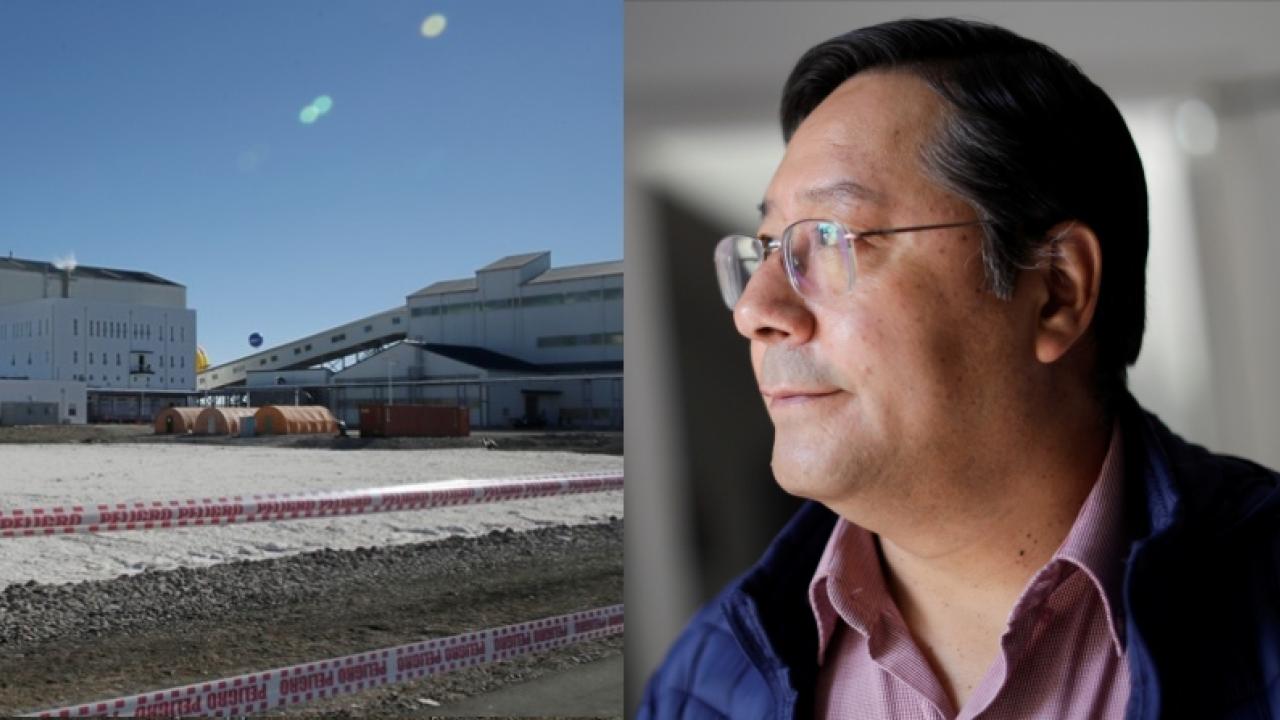

For example, in mid-December of last year, Bolivia signed an agreement with the Russian company Uranium One Group to build the first semi-industrial plant with Direct Lithium Extraction (EDL) technology. Under a phased investment of US$ 450 million, this Kremlin state consortium will operate in the Uyuni salt flat, in turn located in the southern department of Potosí. Karla Calderón, the president of Yacimientos de Litio Bolivianos (YLB), showed optimism about the project and assured that construction would take place in three stages.

The ultimate goal is to achieve production of 14,000 tons of battery-grade lithium carbonate per year. “In principle, it seems good to me that Bolivia has finally opened the possibility for private companies to participate in the lithium industry. Because governments in general do not have the know-how or sufficient technicians to exploit this resource,” says Patricia I. Vásquez, Argentine researcher at the Wilson Center think tank to AméricaEconomía .

A month later, Beijing completed a similar initiative: on January 17, YLB signed a second agreement for the installation of another EDL pilot plant in Uyuni, with the support of the Chinese consortium CBC. Both Calderón and President Arce declared that these projects supported the industrialization of Bolivia. Meanwhile, Ginghua Zhou, representative of CBC, assured that his company was reliable, due to the more than 6 million vehicles worldwide that run on its lithium batteries.

“The motivation of the Arce government is linked to the idea of industrialization and how to project it for the good of the country. It is not surprising that there are Russian and Chinese investments in the lithium sector and battery manufacturing,” explains Jorge Antonio Chávez, an internationalist expert in Asian politics and professor at the San Ignacio de Loyola University (Peru). According to Chávez, the reduction in income from natural gas in Bolivia has been decisive in betting on lithium, due to the expectation of generating a new economic boom like the one experienced during the government of Evo Morales (2006-2019). Although despite the optimism of the authorities, success is not assured.

“The Bolivian government has not carried out the exploitation agreements with much transparency. Although direct lithium extraction technology is faster and uses less water, it must be taken into account that it has not been developed on a commercial level worldwide,” warns Vásquez. According to the researcher, the lithium from each salt flat has different properties and it has not yet been proven that EDL works on a large scale.

Furthermore, the Salar de Uyuni deposits are characterized by containing magnesium and other impurities that make extraction difficult. Therefore, investment should be made in a more specific technology to purify the mineral. In this way, although the Bolivian government and YLB have established encouraging projections for EDL's pilot plants, the truth is that these facilities will serve as a laboratory that demonstrates the viability of the model.

THE PREDOMINANCE OF THE STATE IN THE INDUSTRY

Although Bolivia promotes foreign investment in the lithium industry, its model is still far from the free competition that arises in neighboring Argentina. The State still participates in the entire mineral production chain, following the hydrocarbon model. For José Gabriel Espinoza, economist and former director of the Central Bank of Bolivia , this factor is key to repelling investors from other countries.

“What they are really trying to attract are partners who can lend the money to build plants and operate them, in the best of cases. But in no way are partners looking for partners who want to share the risk. Therefore, there is no investment, but rather they would practically be loans,” said Espinoza for AméricaEconomía .

Likewise, the economist believes that this is a failed attempt by the government to obtain rents from lithium similar to those from gas. It turns out that in the case of hydrocarbons, the maturation of the sector allows a large state capture of rents to be sustainable. “As lithium has not yet been developed and requires a large investment in exploitation technology, this basic premise of the Arce government generates serious disincentives to develop the sector,” explains Espinoza.

Ultimately, the government of the Movement towards Socialism (MAS) generates an expectation in the population that is difficult to satisfy. For this reason, he warns that, in the long term, certain social organizations in Potosí could rise up in protests, seeing that the boom seen in the gas regions of Tarija and Cochabamba is not replicated in their localities.

In addition to excessive pressure on the private sector, Espinoza considers that Bolivia's infrastructure is still insufficient to competitively extract lithium to Pacific or Atlantic ports. Added to the country's Mediterranean nature is political instability, marked by the internal division of the MAS between the supporters of President Arce and former President Evo Morales.

And finally, the absence of a regulatory framework that sets the rules of the game. “For example, we do not know the responsibilities of each actor regarding the provision of water. We also do not have an agreement with the region, because Potosí has historically been very conflictive and jealous of its natural resources,” warns Espinoza.

THE CODEPENDENCY BETWEEN CHINA AND BOLIVIA

The interest of the Xi Jinping regime in Bolivian lithium is not coincidental: Jorge Antonio Chávez highlights that since 1993, China has consumed more oil than it needs. Consequently, the production of renewable energy is important. Chinese demand for lithium is similar to that of the United States for oil: although in 2021, ECLAC revealed that Beijing is the third largest producer of white gold in the world, it is not enough to satisfy the needs of the industry and the domestic market.

At this point, La Paz emerges as an attractive trading partner. “We must remember that Bolivia supports the idea that both China and Russia share that has to do with multipolarity. It is the fact of decentralizing the power of the world from the West to emerging powers like the BRICS,” says Chávez.

However, for the internationalist, it would not be advantageous for Bolivia if only Russian and Chinese companies invested in lithium, without giving access to partners from the United States or the European Union. An economic crisis, marked by the shortage of foreign currency, the increase in country risk and public debt, merit greater pragmatism on the part of the Arce administration.

One of the solutions promoted by the Bolivian government has been the eventual enabling of commercial operations in yuan. The Minister of Economy, Marcelo Montenegro, reported last week that they were also evaluating the entry of a “large Chinese investment bank” to promote operations through the state-owned Banco Unión. Despite promoting itself as the solution to the lack of dollars, José Gabriel Espinoza believes that it will be a non-transparent plan.

“I think it is an anecdotal measure, rather than part of a structured migration plan towards the yuan. Because we do not know what the mechanisms would be for Bolivia to obtain the currency,” says Espinoza. Although exchanging gold from the highland country's international reserves for yuan would be a solution, this would have a very large political cost for the government. Because commercial banks do not make deals or link up with Chinese banks, they do not have access to yuan either.

THE UNCERTAIN FUTURE OF THE MAS

Everything indicates that this is a strategy to lift the Bolivian economy on the eve of the 2025 presidential elections. Luis Arce, who was a trusted man and Minister of Economy of Evo Morales, has now been accused by the former president of ignoring the ideals of the MAS. “Neither Arce nor Morales by themselves could win the presidency in a first election. But the result also depends on the unity of the opposition: the anti-macista vote today is the majority, as long as there is a unified candidacy,” warns Espinoza.

For Chávez, the outlook is also uncertain, because the Bolivian opposition lacks a defined leader: the former conservative governor of Santa Cruz, Luis Fernando Camacho, is in prison. For his part, former president Carlos Mesa, rival of Morales and Arce in the last two elections, has not confirmed his participation in the following year's elections. “But if the MAS manages to resolve this internal difference, it has a chance of winning, because in Bolivia, the empowerment of excluded sectors that the party achieved still weighs,” says Chávez.